We are often told that we can trust printed books, that the process by which their content has been compiled, vetted, and published is a process that filters out subterfuge, half-truths, and misleading gambits. This is not always (or even mostly) the case. Printed matter is the output of human endeavor and humans have biases, make errors, believe untruths, and outright lie in their printed vehicles.

Experienced researchers know this all too well. Once you realize that a book is telling you something that seems suspect, you can research further to determine if it is lying. Those who study the early modern period have a host of examples from which to play with conceptions of veracity and the circulation of ideas. Yet, novice researchers may not know what to do or where to start, and this blog post is for them.

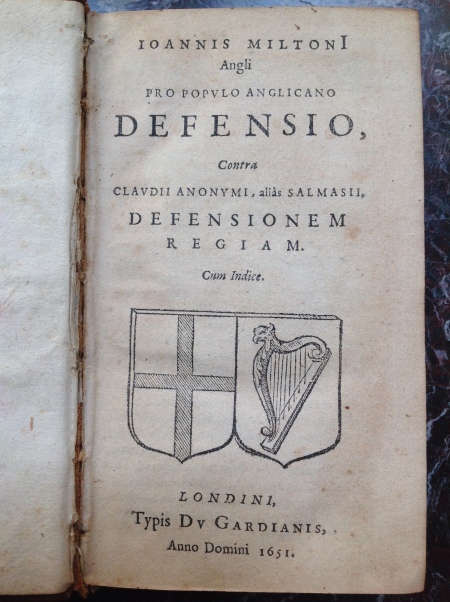

Sometimes, books are in on the subterfuge of their creators, and they are lying for a reason. One example of such subterfuge is the false imprint, or, the lying title page. In a recent undergraduate class held at the Clark, we showed the students John Milton’s Pro populo Anglicano defensio, printed in London in 1651. Why might a book printed in England be written in Latin? How can I find out more?

My first stop is the English Short Title Catalogue (or, “ESTC”), where I searched for the title of the work. The ESTC returned three different possibilities, so I looked more closely at the three to determine which is the one I have in my hands. (This happens often with early modern books that were published in multiple editions or by different publishers.) I looked very closely at the titles of each of them. Since the title page in the Clark copy notes that it contains an index (“Cum Indice“), I am able to determine that this record matches: http://estc.bl.uk/R21409. Happily, the ESTC record has loads of information for me, including that the book was published in Amsterdam, not in London, and was published not be William Dugard (“Typis Dv Gardianis”), but by Louis Elzevier. (See the “Publisher/year” and “General note” fields.)

So, this book is lying about where and by whom it was published. Since it is purporting to be something other than what it is, the next question is why. In this case, the ESTC record helps me again. It gives me a citation to two articles written by scholar F.F. Madan who researched the publication history of this particular work. Thanks to the UCLA Library having a license to access the electronic version of these articles and holding paper copies at various library locations, I have easy access to Madan’s research.

Madan notes that there are multiple editions of this treatise, most of which are not published in London by William Dugard at all. Looking through Madan’s numbered list of editions and variants, the Clark’s copy is clearly no. 6. (I did not need to look this up this, however, since the ESTC record lists it as Madan no. 6. Indeed, if you look at the very bottom of the Clark’s catalog record, you’ll see the notation “Madan 6” as well, but now you’ll know what that means.)

Also according to Madan, this work was “the official reply of the Parliament to the Defensio Regia of Salmasius, which was having a serious effect upon public opinion on the Continent.” (F.F. Madan, “Milton, Salmasius, and Dugard” in The Library, ser.4 vol.4 (1923), p. 119.) And the year 1651 was in the midst of the English Civil War, with King Charles I beheaded in 1649 and Parliament appointing Oliver Cromwell as chair of the new Commonwealth’s Council of State. This work was published amidst intense turmoil over the power of the monarchy, with John Milton responding for the side of Parliament, which hoped to sway public opinion both in England and abroad in its favor. And, the learned European audience for such a work was much more likely to read Latin than English.

What does the publishing history of this treatise, with its Latin text, many editions, and lying title pages, tell us about the purpose of the treatise and the period more generally? To help answer these and similar questions, explore the myriad resources at your disposal via UCLA Librarian Marta Brunner’ s incredibly useful British History research guide.