One of the Clark’s most fascinating annotated books is The excellency of the pen and pencil (1668), a portable drawing manual containing hundreds of manuscript recipes for inks, colors, medicines, and poisons, including the recipe for ink listed in the blog title.

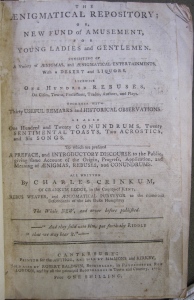

Title page, The excellency of the pen and pencil (1668)

The text was “collected,” as the title page states, “from the writings of the ablest masters both ancient and modern, as Albert Durer, P. Lomantius, and divers others” and is “furnished with divers Cuts in Copper, being Copied from the best Masters.”

Engravings of ears, eyes, mouths, and noses

Besides offering instruction in the nuances of human anatomy, rules of shadowing, and methods of intaglio illustration, this particular copy of the book affords its audience custom content in the form of interleaved manuscript additions. In fact, there is so much manuscript content in the book that its print/manuscript status is best described as “hybrid” (the volume also has two catalog records—one describing it as a printed book, the other as a manuscript).

Printed books throughout the hand-press period could be purchased or bound with interleaved blank sheets of paper to aid in the practice of manuscript annotation. As Heidi Brayman-Hackel notes, “the interleaf radically expands the margin, shifting the proportion between printed text and annotatable space to accommodate the most prolific readers” (Reading Material in Early Modern England: Print, Gender, and Literacy, 142). In the case of the Clark’s copy of The excellency of the pen and pencil, the “radically expand[ed]” margins of the book play host to dozens of contemporary manuscript recipes, many of which relate to the printed text’s emphasis on methods for preparing inks and colors. Here, for example, is the recipe from the title: “To make a Great deale of Ink Quickly and wth a Little Cost”:

“To make a Great deale of Ink Quickly and wth a Little Cost” (page one)

“To make a Great deale of Ink Quickly and wth a Little Cost” (page two)

“Take of ye black that Curriers or Tanners doe black their skinns with, for you may haue much for mony: Then Take ye Gaule of a fish Cal’d a Cuttle, which Costeth almost nothing, & Cheifly in places neare ye sea side, & in eating ye said fish at Divers Times you may keep ye Gaules To Gather. Then mingle ye Gaules with ye Tanners Colour and without Any Other thing you shall haue a perfect Ink. To make it yet better Put to it ye Powder Made of ye Coales of Vitriel, of Gaules, & of Gum. & ye saide Ink, Shall be very Good To print in Copper, Puting to it, a Little Vernix & a Little oyle of Li[m]e, so that it may be Liquid & fitting of it of it self [sic], for to pearce ye better into all manner of Ingravings, & that it may well Abide well vpon ye Paper, without Running Abroade;”

While the quality of this ink may be suspect, the text nonetheless illuminates the resourcefulness of early modern recipes: buy a black dyeing substance cheaply from the leather-tanners, collect galls whenever squid’s on the dinner menu, and if planning on intaglio printing, add a few more specialized ingredients to the ink so it can “pearce ye better into all manner of Ingravings.” Anyone researching the early modern economics of ink manufacture would do well to consult this volume, as it contains several additional recipes for ink, including “Printer’s Ink” and “A very good Receipt To Make Red Ink by,” which is appropriately written in the very red ink it describes.

“A Very Good Receipt to Make Red Ink by”

Yet the manuscript recipes do not simply instruct readers how to create ink; they also offer guidelines for its recovery.

“For Recover old Deeds or Manuscripts”

“Take half a pint of Vinegar, add there to Thirty Gaules Well Bruised and pounded then mix therewith ye Juice of Two Lemmons & foure Onions, & before you make use of them Lett them so stand for Three days you must Use it in this manner. Dipp a feather in ye Bottle & therewith wet that part of ye Writing or Record that is most Illegible & you will soone finde ye Appearance of ye Letters. probat[um]: est: Ja: Godfrey.”

As with several of the volume’s manuscript recipes, the instructions to “Recover old Deeds or Manuscripts” ends with a piece of testimony: “probat[um]: est: Ja: Godfrey,” or “it is proven, [by] Ja: Godfrey.” In other words, “this recipe works, I tried it.” (Whether we are dealing with a “Ja[mes]” or “Ja[ne]” Godfrey is unknown.)

Some leaves, of course, simply provide space for doodling.

Illustration of a head

This later doodle seems to make a facetious reference to the formulaic “How to …” phrase found in many of the book’s manuscript recipes: “How to draw,” with the sketch of a face.

“How to draw”

The binding of this volume, finally, offers several clues for understanding the book as a physical object.

Lower cover

Upper cover

Brass belt hook

The vellum binding, complete with fore-edge flap, has a brass strip at the lower edge of the upper cover, looped to form a belt hook. The volume, in other words, was not only portable in size but physically built to be carried around, its printed and manuscript recipes easily accessible on the go.

Inscription of Samuel Steele

It seems likely that the person responsible for both the book’s portable structure and some of its manuscript content is the Samuel Steele who wrote this inscription on the inside of the vellum fore-edge flap: “Samuel Steele his hand and pen deus Omnipotent.” Whether the “Graf Crow” signature on the title page (see image above) refers to another owner who added manuscript content to the volume is unknown, though it is unlikely Steele was the only contributor. Rather, the multiple hands that inscribed the book’s recipes point to a social tradition of manuscript culture built around the volume, a tradition in which recipes were compiled, tested, and transcribed to create a hybrid book of portable knowledge.

—Philip S. Palmer, 2014–16 CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow at the Clark

!["thes is the sone and a Reg [rain] bowe wth xxvi ti [six and twenty] steres"](https://clarklibrary.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/img_8977.jpg?w=201&h=300)

!["thes be peakockes and yegeles and a puthawk [?]"](https://clarklibrary.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/img_8979.jpg?w=300&h=225)