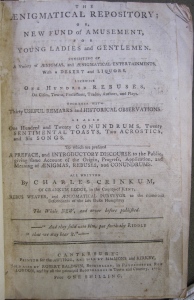

Books of jokes and riddles have a long history. But it’s not too common to find annotated riddle books, with answers added in manuscript by historical readers. The Clark owns one such item, an exceedingly rare copy of a late-eighteenth-century Canterbury riddle book filled with “aenigmas, aenigmatical entertainments,” “one hundred rebuses,” “one hundred and twenty condundrums, twenty sentimental toasts, two acrostics, and six songs.”

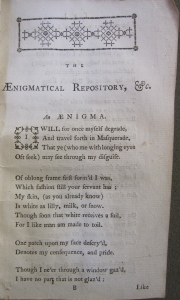

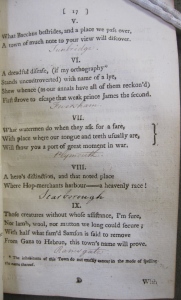

In his preface addressed “To the Public,” pseudonymous author Charles Crinkum claims the “squibs of imagination” featured in his Aenigmatical Repository; or, New Fund of Amusement (Canterbury, 1772) “may perhaps rouse the genius, and awaken the inquiry of the puerile.” The Clark’s copy of this book—one of seven surviving today and the only copy in the U.S.—is also rare because of its contemporary manuscript annotations. These handwritten additions supply answers to the text’s many word games, as in the book’s first engima:

“For I like man am made to toil …

One patch upon my face descry’d,

Denotes my consequence, and pride …

More might be said—but now I’ll ask

My readers to remove my mask.”

The answer, of course, is “The Ace of Spades.”

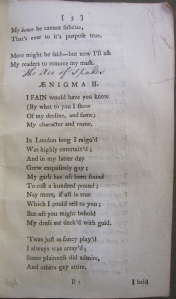

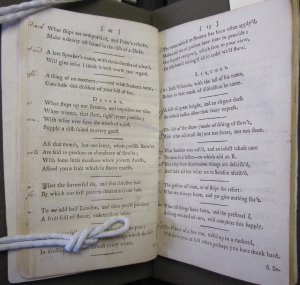

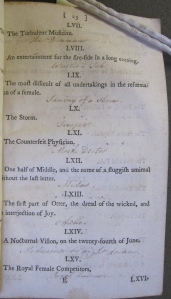

Sadly, the manuscript answers in the “Desert and Liquors” section are largely illegible, thanks to an inexpert trimming and binding job:

But answers in the “Geographical Rebuses” section came through fine:

Apparently readers in eighteenth-century England would see the following—”A hero’s distinction, and that noted place / Where Hop-merchants harbour—a heavenly race!”—and immediately think: “Ah yes—Scarborough!” Modern readers (especially on this side of the Atlantic) have clearly lost the cultural context for deciphering and appreciating the content of some of these games.

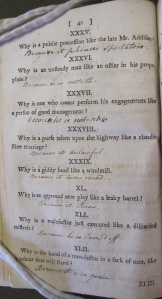

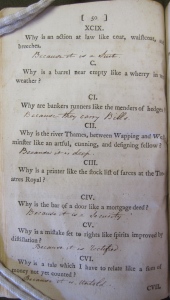

Examples from the “one hundred and twenty condundrums” are more promising when it comes to the interpretive abilities of modern readers, though most of the answers are utterly stupid:

Q: “Why is a purse taken upon the highway like a clandestine marriage?”

A: “Because it is unlawful.” (Reminds me of the bad joke books I read in grade school.)

This one’s a little better:

Q: “Why is a public procession like the late Mr. Addison?”

A: “Because it produces Spectators” (With the obvious reference to Addison’s periodical The Spectator.)

The answers to one section of conundrums consist entirely of play titles:

E.g., “A Nocturnal Vision, on the twenty-fourth of June” = “Midsummer’s [sic] night dream.”

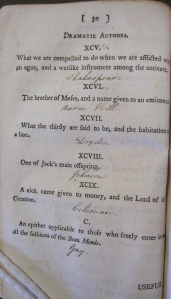

Another page asks readers to fill in the appropriate “Dramatic Authors”:

Q: “What we are compelled to do when we are afflicted with an ague, and a warlike instrument among the antients.”

A: “Shakespeare”

It’s possible these answers were copied in part from A key to The ænigmatical repository (1772), published the same year. (There are only two copies of this even rarer Key, both in the UK and neither digitized on ECCO; thus I have not been able to determine whether the supplied answers were copied from A key or solved by the annotating reader.) A Key is advertised near the beginning of The Aenigmatical Repository: “A Key to the Aenigmatical Part of the following Publication, as also of the Rebuses and Conundrums, will speedily be Published.” But since a few pages have conundrums missing answers …

… it’s very likely the book’s manuscript additions came from the mind of a clever reader, and were not copied directly from a book: those answer-less conundra may have proven a bit too “aenigmatical” to solve, as in,

“Why is a printer like the stock list of farces at the Theatres Royal?”

I’ll leave you to sort that one out.

Editorial Note: The Clark’s copy of Aenigmatical Repository (1772) was on display last week (March 20, 2015) for the ASECS Conference Reception, along with a select group of materials from our rare book, manuscript, and fine press collections.

!["thes is the sone and a Reg [rain] bowe wth xxvi ti [six and twenty] steres"](https://clarklibrary.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/img_8977.jpg?w=201&h=300)

!["thes be peakockes and yegeles and a puthawk [?]"](https://clarklibrary.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/img_8979.jpg?w=300&h=225)